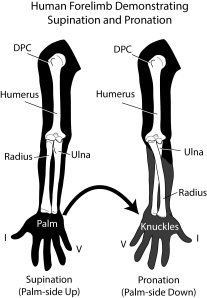

Turn a doorknob and you are taking advantage of what anatomists call pronation and supination: the ability to rotate your hand palm-side down (pronation) or palm-side up (supination). This ability stems from your bone geometry: the radius bone in your forearm is curved can pivot around your ulna, rotating your hand in the process. Drop to the floor and crawl, and your hand is pronated by crossing the radius over the ulna just as it is for mammals which walk on all-fours like elephants, dogs, and cats.

Pronation and supination of the hand by rotating the radius bone over the ulna in humans. (c) 2013 M.F. Bonnan.

In our paper published this week in PLOS ONE, my former student, Collin VanBuren (now a Ph.D. fellow at the University of Cambridge, UK) and myself suggest that most dinosaurs could not actively pronate their hands (that is, turn doorknobs) because their radius could not cross their ulna. Our conclusions were reached after analyzing the bones of nearly 300 specimens representing living birds, reptiles, mammals, and dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus, Apatosaurus, and Triceratops.

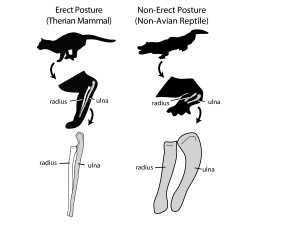

Statistical analysis of radius geometry shows that dinosaurs most often have a straight radius bone with a non-circular head (the part that allows movement at the elbow), a shape similar to those of lizards, crocodiles, and birds. These animals cannot actively pronate their hands, and in lizards and crocodiles this radius geometry is correlated with a non-erect forelimb posture. In contrast, most land mammals show a curved radius geometry that enables the forelimb to be held erect and the hand to be pronated. Mammals like ourselves have a well-rounded radial head that allows the radius to actively swivel around the ulna. Tellingly, the only mammals in our sample that resembled reptiles, birds, and dinosaurs were the primitive, sprawling egg-laying duck-billed platypus and spiny echidna.

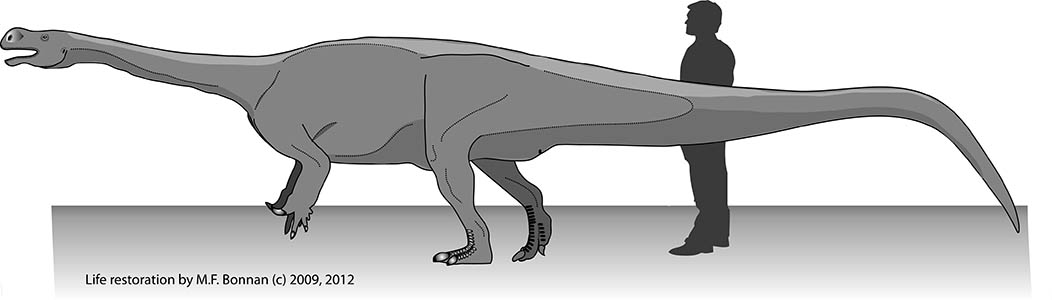

Our findings are significant in that they show dinosaur forelimb posture was not mammal-like and, possibly most importantly, more diverse than previously appreciated. For example, radius shape suggests the forelimb posture and range of pronation in horned dinosaurs like Triceratops was more like those of a crocodile than a rhino. In another example, the radius geometry of the giant, long-necked sauropods such as Apatosaurus don’t comfortably group with living reptiles, birds, or mammals, suggesting that their forelimb postures were achieved in anatomically novel ways. Ultimately, our data strongly suggest that we must re-evaluate our conceptions of how dinosaurs could and could not use their forelimbs.

We can also breathe a sigh of relief: most predatory dinosaurs could not open our doors.

I must give a big shout out and expression of gratitude to Collin — his dedication to this project, through several starts and stops, is what finally saw it through. That we landed this research in a venue like PLOS ONE is that much more of a testament to his perseverance to get this science out there. It means a lot to me that we got this out and into open-access: this represents the accumulation of some of my inferences and hypotheses on dinosaur forelimb posture since my graduate school days. I also want to acknowledge the influence and inspiration of some fellow dinosaur forelimb fanatics, namely Ray Wilhite, Phil Senter and Heinrich Mallison. All are colleagues and friends, and all have also in their own unique ways put dinosaur forepaws front and center — I encourage you to check out their research!

Read our paper, which is open access: http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0074842

Pingback: This Week in Science: September 14-20 2013 | Scientia and Veritas